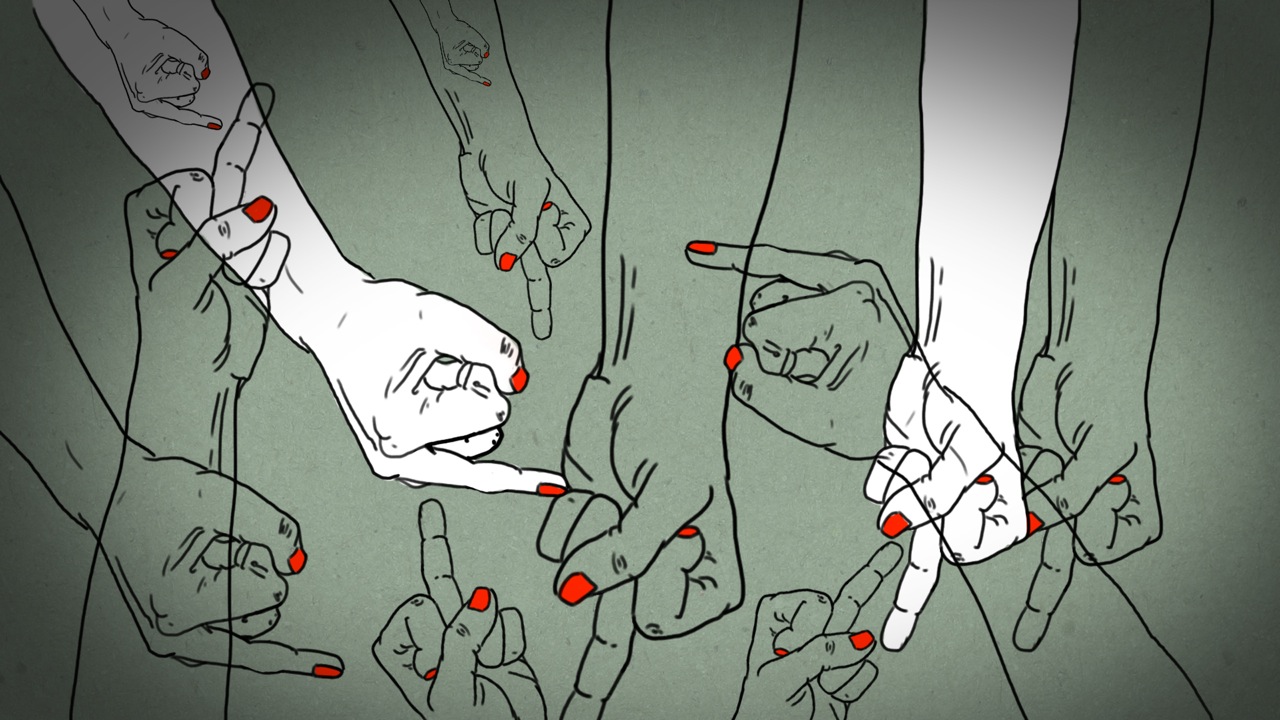

Photography has often been said to carry with it a unique sense of democracy as an artistic medium, giving access to expression based on basic visual ability and tools rather than necessitating formal artistic training. However, this accessibility for minority groups has been and continues to be limited by mainstream artistic institutions and society at large, whose refusal to acknowledge certain kinds of photography as ‘properly’ artistic limits their scope of influence. This has been true for women photographers in general, and particularly true for women photographers who must also contend with racism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, and other forms of oppression. Having few predecessors in the high art world and little representation, young queer femme women photographers are particularly subject to erasure and degradation, necessitating that we build our own communities for artistic expression.

Even outside the art world, lived reality presents numerous issues for young queer femmes, who must contend not only with the denigration of femininity by dominant Western society, especially that which is expressed outside of white patriarchal bounds, but also with the perpetuation of the same problems within their own queer communities. Femme queer women often lack real visibility that is not fetishized for the male gaze, and perhaps in part because of this fetishization, mainstream gay culture tends to brand femmes as somehow less revolutionary (and therefore less queer) because of their gender presentation, ignoring the politics of the individual and of the power of queered femininity. Defining queerness in women by androgynous or masculine appearance not only continues the binary of masculine as default and feminine as the other in a queer context, but also has the real world effect of denying queer femme women easy access to safe spaces without ‘proof’ of their queerness.

So, how are young queer femme photographers creating the communities that are necessary, both emotionally and for artistic expression? These communities can of course exist physically, but lately, they have been built on the internet. Especially for those who lack a functional and supportive community in the physical world (or who may not even be out in the first place), online communities provide a sense of connection to others with similar experiences. In the same way, whether or not a queer photographer has an artistic community for critique and discussion, finding other artists who share connection to your concepts, and having effective ways of spreading your work and receiving feedback, are vital.

This is where websites like Tumblr, a microblogging platform, come in to provide malleable spaces for self-expression on a self-managed basis. Tumblr’s relatively relaxed policy on content allows users a degree of freedom; for example, unlike Facebook and Instagram, Tumblr does not ban or restrict nudity or mature content, thus allowing photographers to post their work in full without fear of having their account deactivated. Since its introduction, groups of Tumblr users have discussed, debated, and promoted feminism, anti-racism, queer issues, and innumerable other issues and sub-issues, often from their own experiences and perspectives. Although these communities have issues with self-policing and harassment from other users, as all communities do, the ability to form networks across immeasurable distance and engage in meaningful conversation about art, life, and the many overlaps in between is absolutely valuable for young women who feel disenfranchised by society because of their sexuality, perspective, and presentation.

This space exists with some equality for professionals and amateurs, and the lines between the two are blurred by the relative accessibility of the venue in which they are presented. Users tend to reblog images because they enjoy the content, rather than because of perceived status, and this has allowed younger artists, students, and amateurs to gain following and visibility basically through online word of mouth.

For example, Patricia Alvarado, a queer femme artist and photography student, gained recognition and visibility for her projects exploring femme identity, bodies, and her experience as a woman of color attempting to imitate white femininity, both from other artists and from other people who related to her concepts. The same is true of various other amateur photographers, and even those who would not necessarily count themselves as photographers but are interested in expressing and representing themselves through photography. The tags for ‘queer woman’, ‘queer femme’, and other related content abound with selfies and personal photography depicting a variety of experiences. It may seem counterproductive for a professional photographer to advocate the inclusion of selfies as artistic photography, but selfies are usually taken to depict how we would like to be viewed by those around us, and in this case, I would prefer that these images were allocated at least the same status as amateur quality photography produced by young white males, often rank with misogyny-lite imagery and lacking expressed concept.

Of course, to imply that the internet at large presents these opportunities easily and without danger would be to suggest that online communities do not suffer from the same dynamics as our societies, which is obviously untrue; internet communities are an extension of our world and therefore subject to the same concerns, rather than existing as a fantasy space outside of lived reality. It is for the same reason, then, that internet communities carry such power: they offer the ability to extend one’s reality beyond physical bounds, to expand options, and to build one’s own community self-selectively. And aren’t the communities we build among ourselves, for the purpose of sharing growth and encouragement, artistic or otherwise, all the more rewarding?

Words and visuals by Kiona Hagen Niehaus