Audio Recording

Winter

I turned the laundry hamper upside down, shaking the quivering body into the planter. A rat, fugitive found in the bathroom of my shared flat, tumbled into the mess of cigarette butts and weeds growing near the trunk of the tree that separated the sidewalk from the parked cars. I’m sorry, I thought, following the rat’s ecstasy as she fled to the faintly fissured gray bark. I couldn’t find a wild place to bring you. A siren howled, blue and white light lit up the underside of the branches that graced the first floor of the apartment building where I took shelter.

I came to the room as winter descended. Opened the double doors to a few pieces of dusty furniture left by past tenants, gray wisps of cobwebs in the corners and the wood floor, spared the hard red varnish found in the other rooms and worn soft enough to catch me. It took me two winters to find my own room in the foreign city, a room I could finally rest in. In that season, I came to know the sounds of the four walls as I rarely left, none of us did. The sun alley outside never ceased. A relentless thoroughfare; a major artery in a car city, the homestretch for men with fast cars who drove to draw attention, to attract witnesses. The white noise of the street came up with the reflection of headlights and overpowered me until I decided the passing of motors waxing and waning recalled the lapping of waves and I slept, finally, like it was the ocean shut out behind the double pane windows. I usually went to bed as early as possible —7pm, if I could finish my work in time. Flossing my teeth, I would hope I had worn myself out sufficiently to not wake in the night talking to him then count the headlights on the ceiling. My own voice would wake me from dreaming, off the walls high and confused, begging someone who was not there, fighting

fighting fighting fighting—

—no one to fight with.

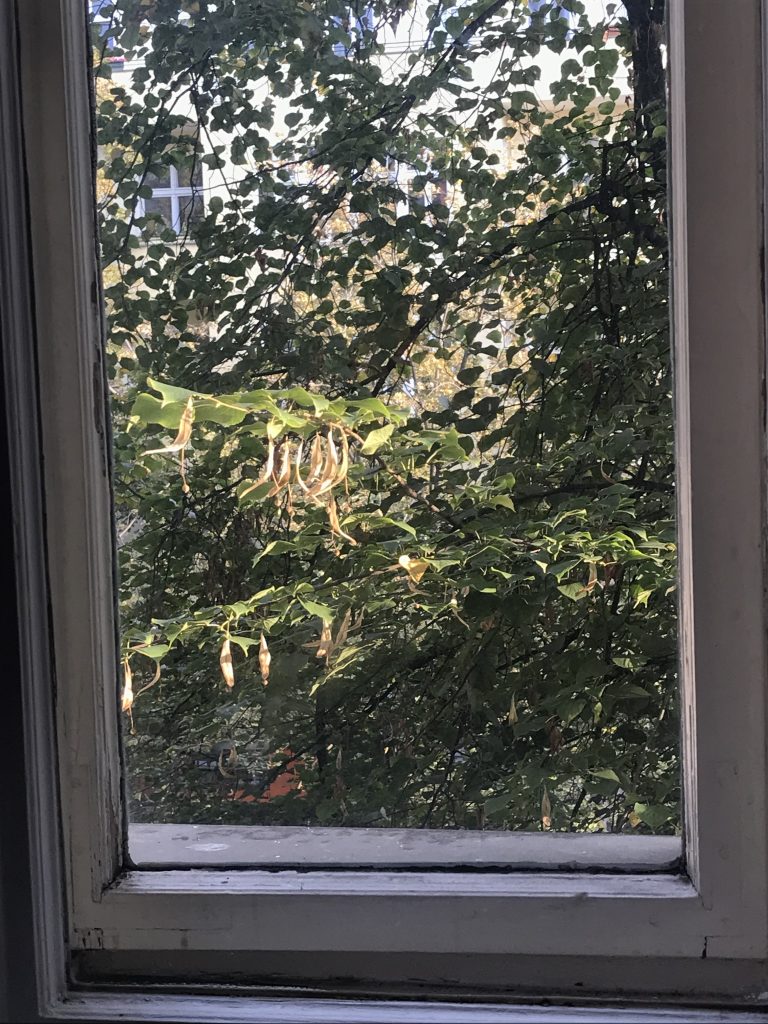

He was never much of a sparring partner anyway, shutting down behind the eyes when I raised my voice, when I threw my fits. Giving up on consciousness in the early evening meant I often rose before dawn like a nun to drink my coffee before the rest of the girls, strangers to ourselves and each other, could form a queue for the single bathroom. I sat at my desk, face the windows, cup in hand, waiting for the small changes in light through the strong horizontal branches that meant the night was over. And so it was in this ritual that I came to know a God grew before me, offering what shelter she could manage in the barren months.

“Do you want help putting up curtains?” He asked once when I invited him over, past my bedtime, to fuck me.

“No.”

I glanced at the yellow lit windows across the sun alley, aware that if I were to focus through the many naked branches of my guardian tree I could witness other humans as they presumptively could return witness of me; staring out at dawn, rarely changing my clothes.

“So you like to be watched.” He sounded half confident, more searching for some enthusiasm in my otherwise utilitarian pursuance. “I guess when there are leaves, you won’t need ‘em.”

“What?”

“Curtains.”

It could be that she heard this suggestion of his. The next morning’s light showed small leaf buds on the fingertips of her delicate branches.

Spring

I had not previously paid much attention to plants. I had an elementary knowledge of how their existence pertained to me: they converted carbon dioxide and sunlight into oxygen through a process called photosynthesis. A very boring word for a remarkable alchemy. Where I grew up, I knew some plants and trees by name, but in the foreign city I still struggled to name items in the grocery store and felt underwhelmed by the natural landscape when it managed to overtake centuries of urban rubble. My view of her from my room on the second floor gave me an unprecedented appreciation.

God tree.

I called her in the morning when she was my first and only vision.

Now that we were familiar, I recognized her sisters lining the sun alley, standing silently in their planters between the streams of cars and people. I craned my neck to witness as their buds grew rounded leaves, asymmetrical hearts with serrated edges. I delighted in the protection and discretion of the leaves, the way they filtered the light they devoured. I sat still at my desk and was often pulled from the demands of the economy, that traded on the currency of my attention, to behold her sheer beauty. The independence of each leaf bud in the spring breeze. I read on the internet that she was widely considered an “attractive” tree, “ideal” for an urban landscape as she could “tolerate” a wide range of adverse conditions including pollution which reasoned her protective stance between humans and the abuses of the busy avenue. I read of her many names; Lipa, Linden, Lipka, Basswood, and was quickly humbled to find I had not invented her worship as the Slavs called her sacred; her name in Polish meant “holy lime”; the name Leipzig comes from her name in Sorbian. She was said to belong to the God Freya, wife of Odin. The Germanic tribes who traveled the marshlands that preceded this city held court Unter den Linden, hoping to call on Freya’s veracity and planted the tree as tribute to this God of luck and love. People found many uses for her flowers and leaves to cure colds, coughs, fever, infections, inflammation, high blood pressure, headache (particularly migraine). Tea made from the blooms served as a diuretic and sedative, producing sweet dreams. People planted the Linden by their churches and cemeteries, so the sweet floral clusters would cover the smell of death.

Summer

In June, she began to drop honey bombs all over the windshields of the fast cars on the sun alley. I presumed the sticky soot her elegant revenge until I learned she was not only the favorite of many winged insects but of aphids, who sucked on her leaf veins for nutrient-rich sap and excreted a sugar concentrate called honeydew. This syrupy sidewalk covering is considered a delicacy by ants, bees and genera of mushroom whose fungal bodies settle on the excreta and as they gorge are vulnerable to burn in the blazing sun, blackening to damage the paint of parked cars. In June, I opened the double pane windows and her dusty pollen swept across the wood floor to suffocate me in my sleep. It was on a night when I awoke to a fit of wheezing and sneezing, suffering some test from my new Lord, that I realized I no longer dreamt of him. I no longer woke up asking the four walls why I had left, why I had been abandoned.

She was similarly non-native to the drained wetlands where this foreign city was so determined to sprawl. Though adaptable, she wouldn’t have chosen such sandy soil that favors the pine tree. She had also traveled. 70-million-year-old fossils of Linden were found on the Siberian Chukotka Peninsula, the easternmost spit of the Asian continent and the site of the land bridge that was traveled by the earliest inhabitants of North America. Travelers on the land bridge took her small seeds in their pockets, and the genus Tilia spread. In Japan, the Ainu people used her bast to weave their clothing, farther east in Ontario, they wove rope from the same fibrous inner bark. Down in Tennessee they sang sweet Basswood and used her body to make electric guitars and people as far south as Florida measured nearly 1500 pounds of pale, saccharine honey in the season of her flowers.

Her oldest sister in Germany stands 25 km west of Munich and is estimated to be over 1000 years old. This Linden was sanctuary to Edigna, daughter of the French King who fled an arranged marriage in favor of an eternal virginity and refuge in the trunk of the great tree. There she lived until her death, instructing the local Teuton tribes how to pray to her lone God while they exalted their Gods of fertility and fought their last battles with the retreating Roman Empire. After Edigna’s death and subsequent sainthood, a sacred oil flowed from her guardian tree (perchance aphids played an unaccredited role in this legend) and when the leaves were harvested at midnight and used to clean the milk dishes, twice as much cream would miraculously appear in the lactoderm come morning. The Christian church that was built in the 8th century literally touching the great Linden’s trunk documented a long-lasting dispute with the “pronounced tree cult,” as the Teutons continued to resist one empire after another claiming their lands and Gods. The Edignalinde was named a national monument in 1983 and thus falls under the purview of Frau Michaela Schleicher at the district office who reported to local news that the Linden now “has to deal with the so-called burn crust fungus.” This aggressive root and butt decay pathogen is known to wound urban trees with its venereal, bulbous spores that harden into a black crust. Impervious to known fungicides, the infection therefore must be cut with utmost care from the heart of the infected tree as Freya watches over.

Fall

The clusters of white flowers transformed into fruits, which then hardened into brown seed pods. Each pod still paired with a secondary ribbon leaf that matured to form what I would soon learn operated like a propeller. The seed and its personal flight attendant left the mother tree one by one on the northern Siberian winds, promising winter. I watched the pods achieve great vertical heights as they dispersed in search of rare soil. Chlorophyll, the pigment responsible for her verdant ability to absorb sunlight, leaked out of her leaves to reveal underlying carotene pigments of yellow and ochre. When autumn stays dry and warm, as this one did, anthocyanins, another group of polyphenolic pigments, produce red coloring in the leaves as they work to protect the tree from the abiotic stress of a stubborn summer. From my desk I watched the sparse golden leaves wag heavy and fall. I mourned the dying of the light. I dated people from the internet. A friend helped me to put up curtains. The anniversary of my own migration to the foreign city falls on a date in autumn. On this day, I walked down the sun alley to the grocery store, a few steps behind a man crooning Hari Krishna into a sputtering, battery-powered microphone. His tinny petition to God rang out over the din of the motors and into the consecrated branches of the Linden tree.

Halle Frost is an editor and writer who sublets a room on Sonnenallee.