Content Warning

This text contains a homophobic slur and mention of sexual violence.

Of course, puberty is a fiction, a way of narrativizing life that had to be invented and written down at some point, and has been written and repeated constantly since. Ronald M. Schernikau chose the hostile and disciplining world of a high school as the setting for his 1980s debut Kleinstadtnovelle (The Small-Town-Novella) to underline once again that the material implications of the Western puberty story on its subjects are very real.

There are specific rooms designed for puberty to happen, classrooms, of course, but also gyms, clubs, skateparks, orthodontists, gynecologists’ waiting rooms, and many more. All of them are shaping the way young people navigate and orientate themselves, segregate pubescents from the rest of society and discipline them to a point where they see no other option in life than complying to the violent heteropatriarchal status quo. leif, the boy the book’s protagonist b. falls in love with, will end up being a good straight man like everybody else. The locker room b. and the other boys share after gym class is a combat zone where “men are trained to beat up faggots and rape women […] where the systematic destruction of happiness takes place.”

The question most people ask is not if, why, or how you’re going to have a puberty, but when you’re supposed to have it normally. Puberty science, advertisement agencies, and TV show writers’ rooms answer to that very question with a temporal norm that shapes our lives in the micro and macro: When should we have this and that experience? How should we structure our lives, look back and forward?

his [b.’s] former german teacher had the audacity to tell him to his face: shut your mouth until you have graduated, after that you can do whatever you want to, don’t risk it all. in university somebody else is going to come and say: do your phd first, do your exams first, get in line first, grow up first and become one of us.

Left out from the dominant narrative of puberty, which relies all too heavily on straight time, is everybody who doesn’t get the timing right: those who have their periods, wet dreams, romantic or sexual encounters too late or too early, those who don’t identify with their gender assigned at birth, who understand transitions of any kind as second puberties, those considered too old to play, or play a role in a subculture, and so many more.

It is said that Schernikau presented Kleinstadtnovelle to his teachers and classmates a couple of weeks before his graduation. Even though I wouldn’t like to follow the 1980s media narrative of him using the novella to hold his own high school to account, it is safe to say that he and the book’s protagonist b., who like the author himself at the time is a queer teenager, endured comparable conditioning by their respective educational institutions.

The novella which follows b. throughout his everyday school life is mostly written in third person. Nevertheless it begins with an “I” that is not marked as an act of direct speech by any of the book’s characters.

“i am afraid. am female, am male, double. feel my body departing from my body, see my white hands, my eyes in the mirror, i don’t want to be double who am i? want to be me, male, female, see only white. i am facing myself, want to reach myself, stretch my arms out towards myself where am i? i see, kiss, hug and intermingle. at some point lea appears, then reappears, and at last he is aware of her. b. senses: he’s lying in bed, it’s morning, his room is blurry, he tries to take it in, feels the movement of his head, doesn’t try to steer it. no hope for a good day today, fuckingettingup, fuckingschool, fuckinglife.”

A similar monologue also closes the book. “I” and b. blend into each other, but remain to some degree independent: Schernikau writes that the “I” wants to “dance like b..” The novella’s “I” is somebody in dialogue, for whom b.’s story seems important; the autonomy of the protagonist, narrator and author is questionable to the extent that it is impossible to say where one begins and ends.

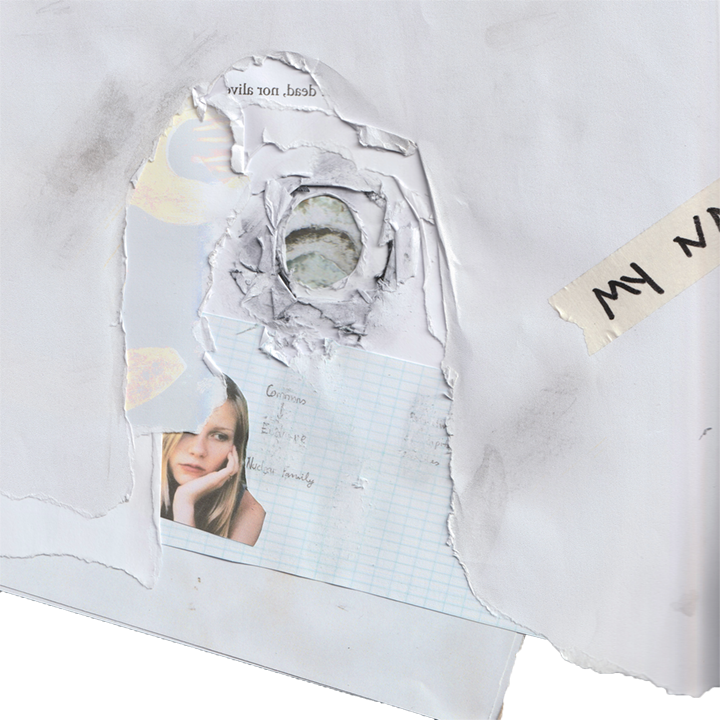

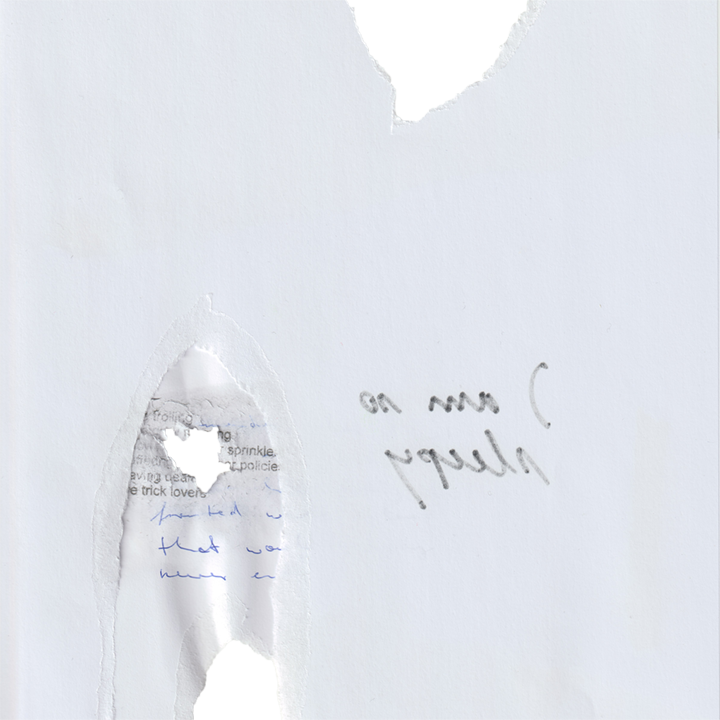

A multilayered collage of abstract paper cut outs on a transparent background. There’s handwritten text on the pages, which is unreadable, because it is mirrored.

Discourses of independence and autonomy are indeed central to the pubescent’s everyday life. While most movies, ads, and songs are written for teenagers – because in the Western world at this point they are still allowed to subject themselves to aesthetic work, to give themselves away, to be unstable, influenced – the job description for the pubescent is clear: grow up, become stable, fixed, autonomous, don’t be influenced by outside forces too much. It is the very permeability and plasticity of the adolescents’ body and mind, though, the openness to all sides, that makes it an object of identification, fascination, and fear, and a key figure in the European novel since romanticism. Schernikau grew up in Lehrte, a small town close to Hannover, Germany and so did Kleinstadtnovelle’s protagonist b.. I am also from a small town close to Hannover, and maybe you are too. Maybe all of us moved or wanted to move to Berlin at some point, chose subculture and metropolis over school life and small towns, something in which at least b. succeeds in doing towards the end of the novel. Puberty poetics is when things get permeable, when I feel my own plasticity and notice the blurring of the line between reader and writer, I am lying in the subway seat, with my hood and headphones on and when I feel I speak through the song that I am listening to, the song speaking through me.

The drive to figure and figure out in visual arts and literature, the forming, sculpting, and destroying of bodies that are also textual bodies and bodies of text that are also bodies, often render artistic practice formally pubescent, even if adolescence isn’t the core subject of a given work. Here poetics, as writing about writing, as a form that brings together aesthetics and politics, lends itself to the investigation of different kinds of pubescent identity.

The feeling that stayed with me after finishing Kleinstadtnovelle was not that puberty itself is the problem, but the hostile conditions in which it is supposed to happen. It is not puberty that causes the trauma that so many – including b., including you and me – want to flee from, but the violence that pubescents face.

–

–

Words and Visuals by Jasper Westhaus

Jasper Westhaus (*1996 in Hannover, Germany) is an artist, writer and researcher based in Amsterdam. They write essays, poetry and texts in-between in English and German. You can find extended writing about puberty on their blog pubertypoetics.net.