Audio transcription:

CW: Without going into details, please note that the text addresses themes of sexual, emotional, and spiritual abuse.

The Context

In the beginning of 2020, a former personal attendant and long-time chief secretary of Yogi Bhajan – Pamela Dyson Smith – published a book entitled Premka – White Bird in a Golden Cage in which she writes in detail about her 16 years living with and working for the founder of Kundalini Yoga. In her memoir, Dyson Smith shares insight to her private relationship with Bhajan and the clan-like power structure of the community surrounding him in the ’70s and ’80s. She describes the sexual abuse and emotional manipulation she suffered at his hands.

Although Dyson Smith wasn’t the first one to come forward with allegations of sexual abuse against Bhajan, this was the first time they were publicly heard and widely received. A facebook group was founded and, in the spirit of the #MeToo movement, over 100 other women (and counting) came forward and shared their stories. Most of these women are former members of his organisations, have lived in his community, studied with him, and worked for him between the ’70s and the 2000s.

The LA Mag published a great overall synopsis that I recommend for further reading. Premka, aside from the specifics about Kundalini Yoga, gives an important insight into the psychology of a white woman during the North American New Age movement in the ’60s and ’70s. Understanding the ‘lineage’ of white people’s obsession with Eastern practices is, in my opinion, important for any white Westerner who practices yoga.

In response to the allegations, the Kundalini Yoga organisations of Bhajan – 3hO and Kundalini Research Institute (KRI) – ordered an investigation by an independent party, which in March 2020 started conducting interviews with survivors and witnesses. The full report was concluded and published in mid August 2020 (CW: The report contains graphic description of sexual abuse and child abuse). For a brief and less detailed sum up, see this article on Yoga Journal.

Since then, none of the teachers I personally have studied with during my teacher training at KRI have reached out privately or positioned themselves publicly, as far as I know. I have seen high-ranking Kundalini Yoga teachers lead slander campaigns against the alleged victims. I have also heard of Yoga studios and individual teachers who made public statements in solidarity with the survivors. What seems to be most common, though, is to “separate the teachings from the teacher,” or simply to remain silent. These teachers see no reason to speak to or inform their students about this. To me, this kind of politic is a severe form of spiritual bypassing. No one should have to sit with this alone. Difficult topics like this are exactly where we put Yogic philosophy to practice, both personally and collectively.

My Perspective

When I heard of the book and the allegations back in 2020, I was not surprised. History has taught us not to trust (older) men in power, let alone a “Guru” who emerged in the ’60s. The cult around his persona disturbed me during my month-long teacher training in his former ashram in New Mexico in 2017, and I would not have done the training if he were still alive. However, until I read Premka, it felt legitimate to me to separate the teachings from the teacher, given that I had been taught that Kundalini Yoga was an ancient Indian tradition that had been passed down orally for more than 8000 years, which Bhajan simply brought to the West.

I had always focused on trying to get a deeper understanding of the lineage, philosophy, and culture of the teachings. I studied the tantric concept of kuṇḍalinī and the Sikh Mantras used in the meditations and exercises. As a queer person with an intersectional politic doing a teacher training at an ashram, I mostly struggled with and spoke up against the ignorant heteronormativity and transphobia, zero awareness for cultural appropriation, and unchecked white privilege in a predominantly white group of trainers and students.

When I read Premka, I was shaken by the extent and the subtle, systematic nature of abuse of power. Reading the book made me understand how Bhajan’s sexual and emotional abuse does not stand alone, but is linked to a much larger system of abuse of power. And this system pervaded all areas of his personality, including his teachings. The way Bhajan set up and manipulated a clan of followers — keeping a circle of exclusively women closest to him, for example — cannot be viewed in isolation from the sort of divine authority he claimed over the practice as a “Guru.”

Deconstructing The Origin Myth Of Kundalini Yoga As Taught By Yogi Bhajan

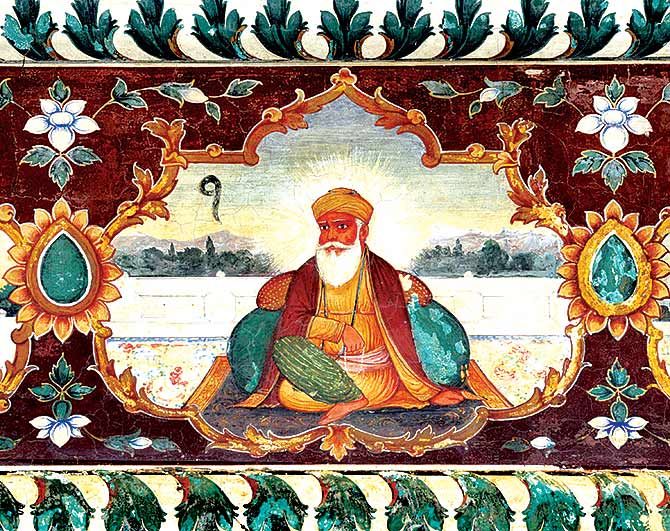

Part of the misleading origin myth that Bhajan constructed is the story that the practice of Kundalini Yoga is traditionally tied to Sikhism. I believed this too, even though I wondered why my attempts to find ancient or current Punjabi Sikh sources containing the practice of Kundalini Yoga only led me back to Bhajan and his organisations. The reality is that Bhajan, being a Sikh, tied these two together and made up “the Golden Chain of teachers,” through which he said Kundalini Yoga, including all the yoga sets (kriyas), had been passed down to him.

Before he came to the US in the late ’60s, Bhajan had worked as a customs officer in Delhi, studied yogic practices with Hatha Yoga teachers like Swami Dhirendra Brahmachari (among others), and practiced Sikh religion and Devotional Chanting under the guidance of the Sikh Guru Maharaj Virsa Singh. As the story tells, Bhajan took American Hippies off drugs by getting them high through other means. The out-of-body effects of his practice are connected not only to what he taught but to the way he taught these ancient techniques. There are so many other ways his teachings could be practiced. The rigidity and formality of how teachers are trained has limited personal agency and intuitive capacity of practitioners. I think it’s time to experiment and explore. The teachings cannot be separated from the teacher. But we need to separate the teacher’s authority from the practice and how we engage these tools.

For anyone practicing Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan, I recommend the detailed research article From Maharaj to Mahan Tantric – The construction of Yogi Bhajan’s Kundalini Yoga by history scholar and former Kundalini Yoga practitioner Philip R. Deslippe. Pointing at the interconnection of white ignorance and Bhajan’s abuse of power, Deslippe writes this:

“Yogi Bhajan was free to revise the understanding that his students had of Kundalini Yoga, its origins, and his own personal lineage, since like many other charismatic leaders within New Religious Movements, his word was accepted prima facie by his followers without any need for outside confirmation. (…) On the first trip to India, none of Yogi Bhajan’s students spoke Punjabi or were familiar with Sikh customs, let alone with Indian culture at large. (…) Like a small restaurant that places mirrors on opposing walls to create the appearance of depth, it is from the singular person of Yogi Bhajan that all information about the lineage and practice of his Kundalini Yoga originates.”

White Washing And Its Consequences For The Sikh Community

What Bhajan branded as Kundalini Yoga is in fact a complex mixture of Indian traditions from very distinct origins and contexts: the concept of kuṇḍalinī and the system of the chakras, stemming from tantrism, (Hatha) Yoga philosophy and practice (which is connected to Sanskrit Mantras), and Sikh religious practice that uses Gurmukhī Mantras for devotional chanting.

While all ancient practices and traditions are the result of complex and collective processes of cross-pollination, it is the concealing, fabricating, and passive participation via ignorance that created the harm and contributed to a large scale whitewashing of the traditions contained in Bhajan’s Kundalini Yoga. The community of Punjabi Sikhs worldwide have had to deal with enormous consequences:

“We are one of the most misunderstood, misrepresented faiths”, says Sundeep Morrison, a queer Sikh activist currently working on a documentary about 3HO and its consequences for Punjabi Sikhs, in this article on The Juggernaut: “About 60% of Americans don’t know what our faith entails. Yogi Bhajan centered whiteness in Sikhi, he made up his own pseudoreligion, which I consider a cult. I don’t call it ‘white Sikhi,’ I call it ‘Bhajanism.’ (…) He conflated an over 500-year-old faith [Sikhism] with an over 5,000-year-old practice [yoga], and presented it to white people and centered whiteness in it. (…) Kundalini Yoga as a brand has a larger voice in white America than the 500,000 Sikhs who live in the U.S.”

Finding Agency

Knowing what I know now, I have come to understand that the struggles I experienced during my teacher training and the Kundalini Yoga community’s history of abuse are intricately interconnected. The unwillingness of white Westerners to critically interrogate our relation to Indian (or any form of non-Western) practices and actually do the work to understand the complexity and multiplicity of Indian culture, has solidified the myth around Bhajan’s Kundalini Yoga and is upholding complacency around the abuse.

In consequence of what I’ve come to understand, I started to integrate changes in order to align my values with my practice and the classes I facilitate. At the beginning I continued to use elements from Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan, but completely removed his authority from how I would use these tools. I stopped using his meticulously timed and structured kriyas in their original form and started to create my own sets. Modifying exercises, adding and removing elements, playing with timing, speed, and duration helped me release the inhibition and external authority I was still holding. I studied what the exercises do to me – in order to apply and modify them from a place of agency over my body and according to my own embodied experience, intuition, and intention. I included other yogic and non-yogic practices and began to study yoga and its philosophy through other sources, prioritizing non cis-male contemporary teachers, practitioners, and philosophers of Indian descent. (Check out the podcasts Yoga Is Dead with Jesal Parikh and Tejal Patel and Let’s Talk Yoga with Arundhati Baitmangalkar). The continuous study of ancient yogic philosophy and history through various angles has become an integral part of my practice.

When using Sikh Gurmukhī Mantras I now only chant them on their own and in seated meditation, as originally practiced in Sikhism. I stopped tuning in to practice with what Bhajan called the Adi Mantra (ONG NAMO GURU DEV NAMO) as it’s not clear to me where that comes from. I couldn’t find it anywhere in Sikh sources and it seems likely that Bhajan created it himself. Instead I have turned to Sanskrit Mantras. I have also experimented with creating English mantras, using simple sentences like “I am Love” … but I haven’t really found my way with that yet. The question about how to incorporate mantras and which mantras to use is still keeping me busy. Chanting Mantra is an essential part of yogic practice and simply moving away from ancient Indian mantras doesn’t seem like the right answer to the question of how to avoid cultural appropriation.

As I am making this edit, I have thrown all my Kundalini Yoga Books into recycling, since I realized that all of the legitimate elements in Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan can be found in other sources and practices. And the joyfully random elements I always loved most, like one of his exercises that instructs you to “Lie on your back and jump your body like a fish in a frying pan” I can easily come up with myself. When it comes to holding the grief that some of these changes have brought about, it helps me to remember that what I lost was never mine to begin with.

List of Links:

Link 1: Premka – White Bird in a Golden Cage (Book)

Link 2: Yogi Bhajan Turned an L.A. Yoga Studio into a Juggernaut, and Left Two Generations of Followers Reeling from Alleged Abuse

Link 3: An Olive Branch

Link 4: Full report by An Olive Branch

Link 5: Less detailed report from Yoga Journal

Link 6: Dhirendra Brahmachari

Link 7: From Maharaj to Mahan Tantric – The construction of Yogi Bhajan’s Kundalini Yoga

Link 8: Sundeep Morrison

Link 9: Article on the Juggernaut: How a Cult-turned-Corporate Hijacked American Sikhism

Link 10: Yoga Is Dead with Jesal Parikh and Tejal Patel

Link 11: Let’s Talk Yoga with Arundhati Baitmangalkar

Words and Header Image by Xenia Taniko

Xenia Taniko is an artist, performer and choreographer based in Berlin. Their artistic practice spans performance, music, magic practices, community building and participatory formats. Working with their body as main portal, they’re currently deeply invested in practices of non-doing and un-doing internalised capitalism. To find out more about their regular Online Community Yoga and Meditation Classes, sign up here.