***

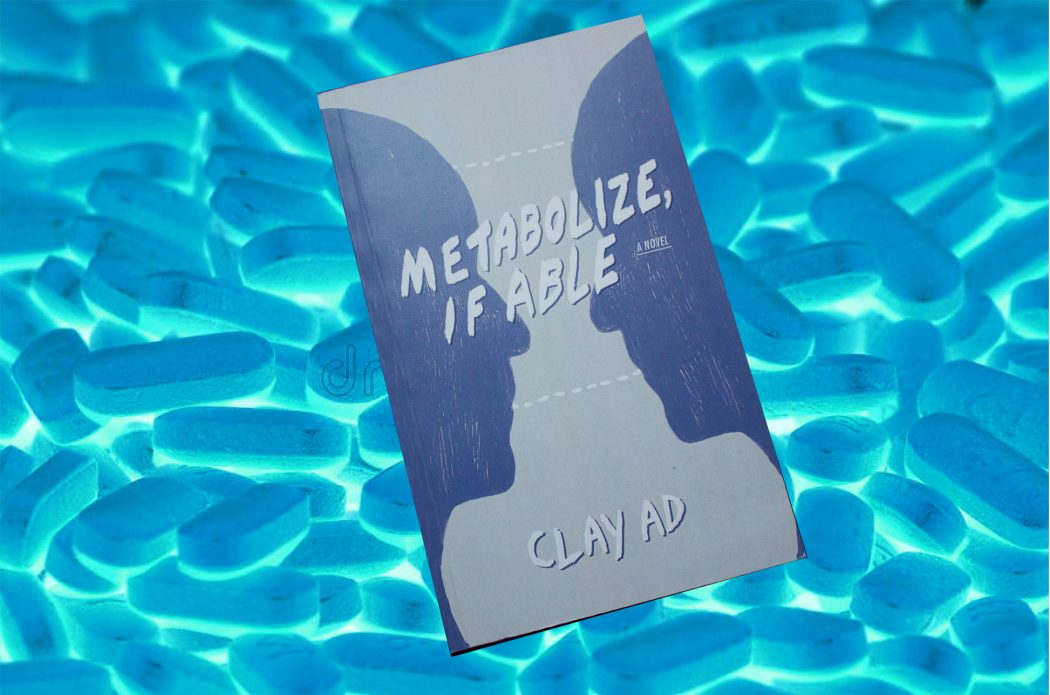

Metabolize, If Able (Monster House Press, 2018) by Clay AD

***

“There should be no therapeutic act that has not been previously established as a revolutionary act,” declared Wolfgang Huber, an assistant doctor at Heidelberg University and founder of the Socialist Patients’ Collective (Sozialistisches Patientenkollektiv), in 1970. “For the patient there is only one pragmatic way to combat their illness: namely the dissolution of our pathogenic, corporate-based, patriarchal society.”

The Indianapolis-born, Berlin-based writer and self-described “sicko” Clay AD, whose first novel—Metabolize, If Able—was recently published by Monster House Press in the USA and Arcadia Missa in the UK, is an incandescent queer inheritor of this fundamental insight. In the Epilogue, they explain: “Dear reader, / This book was written on the slowly compounded rage of navigating the medical industrial pharmaceutical system for the past ten years of my life. It was a response to my allopathic doctors … simply calling me crazy and suggesting I should get evaluated for an anxiety disorder instead of listening to my needs.” The protagonist of the novel is a clone, a subaltern living on the periphery of a fascist metropole in a relation of extreme dependence upon Bio*Corp corporation doctors.

AD further confesses in the postscript that they felt ambivalent about birthing Metabolize, If Able in the aftermath of Trump’s election (a world whose dystopic character has grown inescapable). They are “deeply tired,” they wrote in 2016 in their personal journal, “of writing about dystopias.” But it is an excellent thing for on-the-ground utopianists and queer feminists everywhere that Metabolize, If Able was, in fact, published. Not least because, as with all thoughtful dystopias, there is a strong undercurrent of critical utopianism at the heart of this text.

The book is, among other things, a tribute to “Jane,” i.e. the Jane Collective which illegally performed abortions in Chicago between 1969 and 1973; an exploration of queer mothering and reproductive ethics; a fictive ethnography of the lives of a subjugated population of state-sterilized clones; a collage of somatic “meditations,” instant messages, online correspondences, and screenplay dialogue; and a narrative of queer intragenerational intimacy-turned-resistance, set in a dystopian future ruled over by the Bio*Corp regime.

In AD’s fascoid scenario, the medically oppressed are clandestinely perfecting autonomous herbalism; the clones are covertly refusing to swallow their pills; and everywhere there are whispers of sabotage, of underground networks of rebels. Unmistakably, the humanoid guinea pigs are conspiring with their non-sick, human allies to rethink care in new and nuanced guises. Fundamentally, then, this powerful new fiction is an incendiary homage to the historic slogan “turn illness into a weapon.” As AD’s fictional screenwriter asserts in their script notes, the historic originators of that slogan, “SPK questioned the patient/doctor paradigm and ultimately called for an overthrow of the ‘doctor’s class.’” And AD’s concerns are passionately shared and have lately been echoed by twenty-first century sickos around the world.

When the collectively authored agit-prop text (Agitationsschrift) SPK: Aus der Krankheit Eine Waffe Machen was published in Munich in 1972—complete with a foreword by Jean-Paul Sartre, praising the group for “radicalizing anti-psyschiatry”—it laid the theoretic groundwork for an insurrection against “iatro-capitalism” (i.e., medical-psychiatric or pharmacological capitalism) that has carried on, in thought and deed, at the margins of Euro-American societies ever since.1

For example, half a century after Huber’s pronouncement, Anne Boyer published The Undying, a cancer memoir and an indictment of “the capitalist medical universe in which all bodies must orbit around profit at all times.”2 The UK-based Institute for Precarious Consciousness called for a revival of consciousness-raising affinity groups, and affirmed, in its 2014 manifesto “We Are All Very Anxious,” that contemporary “precarity leads to generalised hopelessness; a constant bodily excitation without release.”3 The similarly influential essay “Sick Woman Theory” was published, proposing the figure of the Sick Woman as a revolutionary subject (N.B. the identity and body in question can belong to anyone—for instance, “a black man killed in police custody”). The author of the latter, self-described anticapitalist psychonaut sorceress Johanna Hedva, insists that “‘sickness’ as we speak of it today is a capitalist construct [every bit as much as] its perceived binary opposite, ‘wellness.’”4

In 2018, Metabolize, If Able joined the ranks of this imaginative tradition of somatic resistance, mad pride, care sluttery, and disability liberationism. Their medium is ostensibly fiction but, as noted, Clay AD—a healer and bodyworker living in Berlin—explicitly grounds their imagined clone insurrection in their own subjectivity and experience of iatro-capitalism. Indeed, the relation between the normal “now” of present reality and the catastrophic “tomorrow” of the clone-ocracy that is “Bio*Corp” is intentionally called into question. For instance, AD historicizes their claims with reference to the European witch-hunts: “Like / this has all been happening for / centuries. The real healers were / killed off one by one and no one stopped / the series of exterminations, just / let them all burn and burn and let /all the knowledge burn too.”

Another of AD’s in-text voices, the fictional clone, Ruby Penny—an adult child of our protagonist clone, who “spawned” her on a bus—likewise articulates an understanding of catastrophe not as an event, but (echoing the tenets of We Are All Very Anxious) an environmental epoch. In the artist statement for her movie Turn Illness Into A Weapon, Ruby writes: “Sometimes crisis is framed as an abrupt moment of reckoning, but for us it is clear it is always a chronic condition.”

… most days hold an endless repetition of unspoken terror, that life, in its daily, violently structured monotony, will never alter its frame. However, by making this film we stepped out of our given lives and refused to turn back. Wove our collectively inherited toxicity to make a representation of our rage.

Here, Clay AD is palpably willing into existence a militant film—as yet unmade, I presume—that might actualize the insurrectionary potential of the “sick” and change the world. It is safe to assume that the movie in question is not the one about the SPK that was released, coincidentally, at the same time as AD’s book—namely, The SPK Complex (Icarus Films, 1h55min), directed by Gerd Kroske—but which has been thunderously denounced on the website of the present-day SPK.

Throughout Metabolize, If Able, the reader is offered vignettes that are clearly drawn from life: about dysphoria in the medical examination room; cohabitational love that doesn’t play out in a classic couple-form; non-heteronormative gestationality. The result of this intimate method is a debut novel that reanimates the topics of sickness and collective corporeal vulnerability in a poetic and accessible way.

Not to mention an immediately politically relevant one – after all, in the age of coronavirus, the arts of epidemiological neighborliness and community mutual aid have had to be ultra-rapidly improvised and learned, especially amongst the atomized human landscapes of the so-called western world. It was prescient in that sense that, in Spring 2019, well before the Covid-19 epidemic took hold in Europe and North America, Metabolize, If Able was named as a finalist in the 31st Lambda Literary Awards for LGBTQ Sci-Fi, Fantasy, and Horror.

The present pandemic is an excellent time to engage with thoughtful treatments, like this one, of (to quote AD), “the undeniable reality that we are contingent even from afar.” Perhaps we may still, as a species, discover that—in Johanna Hedva’s words—“once we are all ill and confined to the bed, sharing our stories of therapies and comforts, forming support groups, bearing witness to each other’s tales of trauma, prioritizing the care and love of our sick, pained, expensive, sensitive, fantastic bodies, and there is no one left to go to work, perhaps then, finally, capitalism will screech to its much-needed, long-overdue, and motherfucking glorious halt.”

Review by Sophie Lewis

Header Image by Clay AD

Sophie Lewis is a queer degenerate and utopian theorist living (and free-lancing, as a teacher and writer) in Philadelphia. Their first book Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family came out in 2019 with Verso Books.

Clay AD (they/them) is a Berlin based interdisciplinary artist, writer, and somatic bodyworker. Their first novel, Metabolize, If Able (2018) is available through Arcadia Missa Press UK and was named a finalist in the 31st Lambda Literary Award for LGBTQ Sci-Fi, Fantasy and Horror.

1 SPK: Aus der Krankheit Eine Waffe Machen. Eine Agitationsschrift des Sozialistischen Patientenkollektivs an der Universität Heidelberg, C Trikont Verlag, 1972. socialhistoryportal.org/sites/default/files/raf/0019720400.pdf

2 The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care, Anne Boyer, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2019.

3 “Six Theses on Anxiety and Why It is Effectively Preventing Militancy, and One Possible Strategy for Overcoming It,” Institute for Precarious Consciousness, April 4th 2014. weareplanc.org/blog/we-are-all-very-anxious

4 “Sick Woman Theory,” Johanna Hedva, Mask Magazine, 2015. maskmagazine.com/not-again/struggle/sick-woman-theory