Audio transcription:

Letter.

Greetings and God’s blessing upon you my dear husband, Monsieur d’Allee, on this, the 2nd day of June, the year of our Lord 1321.

I deliver bad news, of which, I am sure you are already aware. Rumours travel quickly which has certainly been our undoing. In truth, I believe word of our plot had already begun to spread when we first secured the poison some time ago.

John’s fate has been most unfortunate. He was caught almost immediately by the city guard, as no amount of clothing can disguise his deformities. He should never have been brought along; his illness is too visible. As you know, leprosy has yet to disease my face and I was able to evade detection a little longer. I managed to throw a few handfuls of powder into a third well before I was seized upon. The guard grew suspicious of my gloves and ordered me to remove them. Once dispensed with—my abominable fingers revealed—there was little doubt as to the true nature of my disease.

I would have liked to live to see everyone live like us—contaminated, cast out, living under charity. How they complain about nothing! Our lives are worth more in illness than theirs in health. My visions of healing are of a world made equal through our illness, not from cures or new medicines. Remember what sickness has taught us: patience, resilience, and the importance of friendship with those who are oppressed.

Please give my remaining property to Meggy before it is possessed by someone else. It is unfortunate that the claims unjustly laid against her stuck. Perhaps the money will be enough to secure a letter from an honest doctor and clear her name of leprosy. I pray for dear Meggy daily. I am grateful to God for having met her and will greatly miss her company. It is not just that she should have to suffer such moral penalties alongside the rest of us, now that our initial plan has failed and the sick remain persecuted.

And now, dearest Henri, I am about to be taken up to the square to suffer the flames. Cleansed by fire, the townsfolk say, but I hope instead that my disease spreads and the revolt will live on through my ashes. I fear the violence yet to come; I pray for you and the others at the leprosarium. But do not forget our purpose: make them all sick.

I wish that I wrote to you instead of our success, not of our failure, and that we would meet again in happier circumstances. But such things are for the Lord to adjudicate. Farewell, my kind Henri. How sad I am that we will never speak again except through this letter. But I take comfort in the knowledge that our souls shall be forever joined in illness.

I go to Lazarus now.

Fare thee well, dear heart.

Anes

Post-script.

A note on language: I have chosen to use person-first language rather than identity-first language here. Like other disability slurs, the word “leper” carries a heavy history of stereotypes, stigmas, and violence.

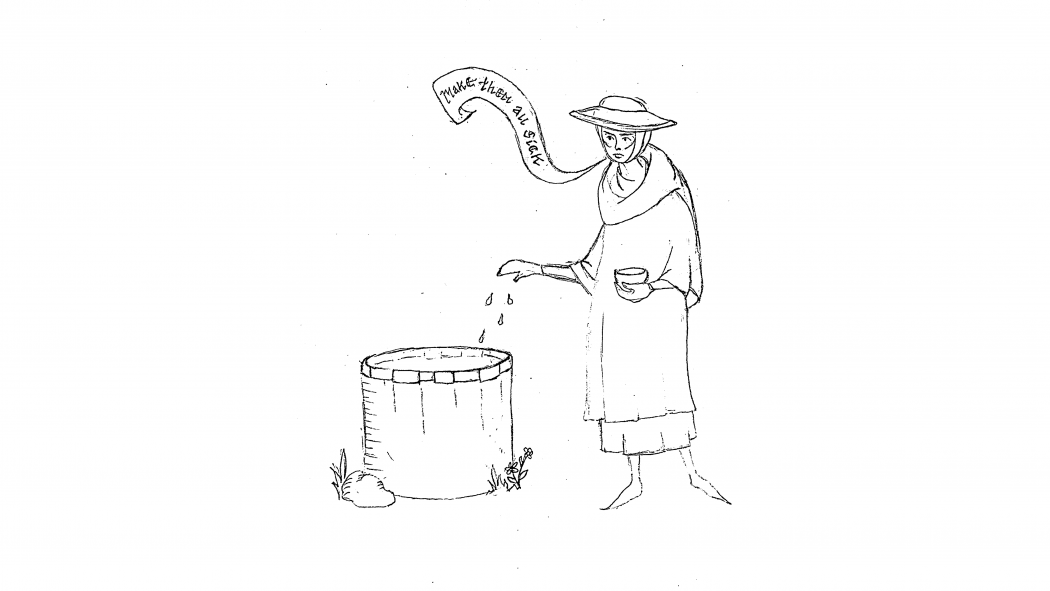

The above letter is a fictionalized account of the events of The Leper Plot of 1321, where people with leprosy were the leaders of a revolt. The letter is not historically accurate. If it were, Anes would be the victim of a disastrous rumor rather than a member of a marginalized community fighting back against oppressive systems. In this reimagined version of events, the sick attempt to overthrow the healthy (rather than the other way around).

In reality, in 1321 France, people with leprosy were accused of plotting to poison wells and other water sources in various towns across the country, supposedly intending to pass their illness to the healthy population. While these allegations are suspected by scholars to be untrue, the charges stuck, leading to the arrests of many people with leprosy. Foreigners with leprosy were rounded up and tortured or murdered while locals were to continue living in leprosaria, or leper communities, and ordered not to travel or face similar outcomes. Jews and Muslims were also brought into this plot, guilty or not, and were subject to comparable levels of violence. Like the leper communities, Jews and Muslims held uneasy positions in Christian society and the plot served as grounds to further discriminate against them. The rumours also acted as an excuse to seize property from, murder, and further segregate people with leprosy from the rest of the community.

Leprosy proved difficult to diagnose for most physicians. The tell-tale symptoms could take decades to appear, depending on a person’s resistance to the disease. Medieval diagnostic techniques were more useful in identifying advanced cases where symptoms were more visible, such as changes to the hands and face. Because leprosy proved challenging to identify, people were fearful of undiagnosed or non-visible leprosy in their communities, furthering their anxieties around infection, contamination, and disease. This anxiety led to false accusations, whether by their neighbours or their enemies, and an accusation could have devastating effects. Leprosy was also believed to be highly infectious when, in reality, the rate of infection was relatively low. Once diagnosed, many people with leprosy lived in leprosaria isolated away from the healthy population and under the care of charitable institutions.

Similar to views of illness and disability today, leprosy was often seen as an indication of moral failure or guilt—the problem of the individual. These views were part of a larger moral economy at the time, one where disease, sin, and corruption were closely linked. If the plot of 1321 were true, how might our histories of illness and the treatment of our sick communities have changed? There aren’t many moments in history where the sick have revolted against the healthy, but perhaps we can commit this to our archives nonetheless. Like Anes in the letter above, I hope that illness one day changes the world, just as illness has changed hers (and my own).

Words by Olivia Dreisinger

Images by Anne Tastad

Sound by Olivia Dreisinger, Anne Tastad, and Tristan Douglas

Olivia Dreisinger is a sick scholar specializing in all things disability. She is the director of two documentaries: Handler is crazy and disabled!. She lives and works from her bed (and likes it that way).