Audio Transcription:

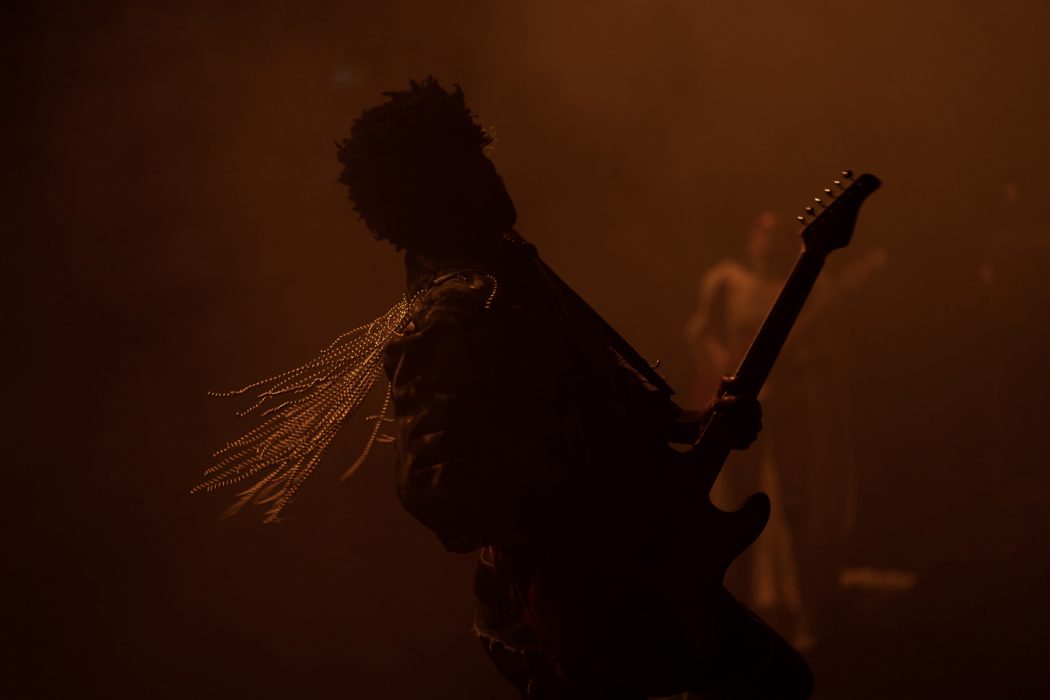

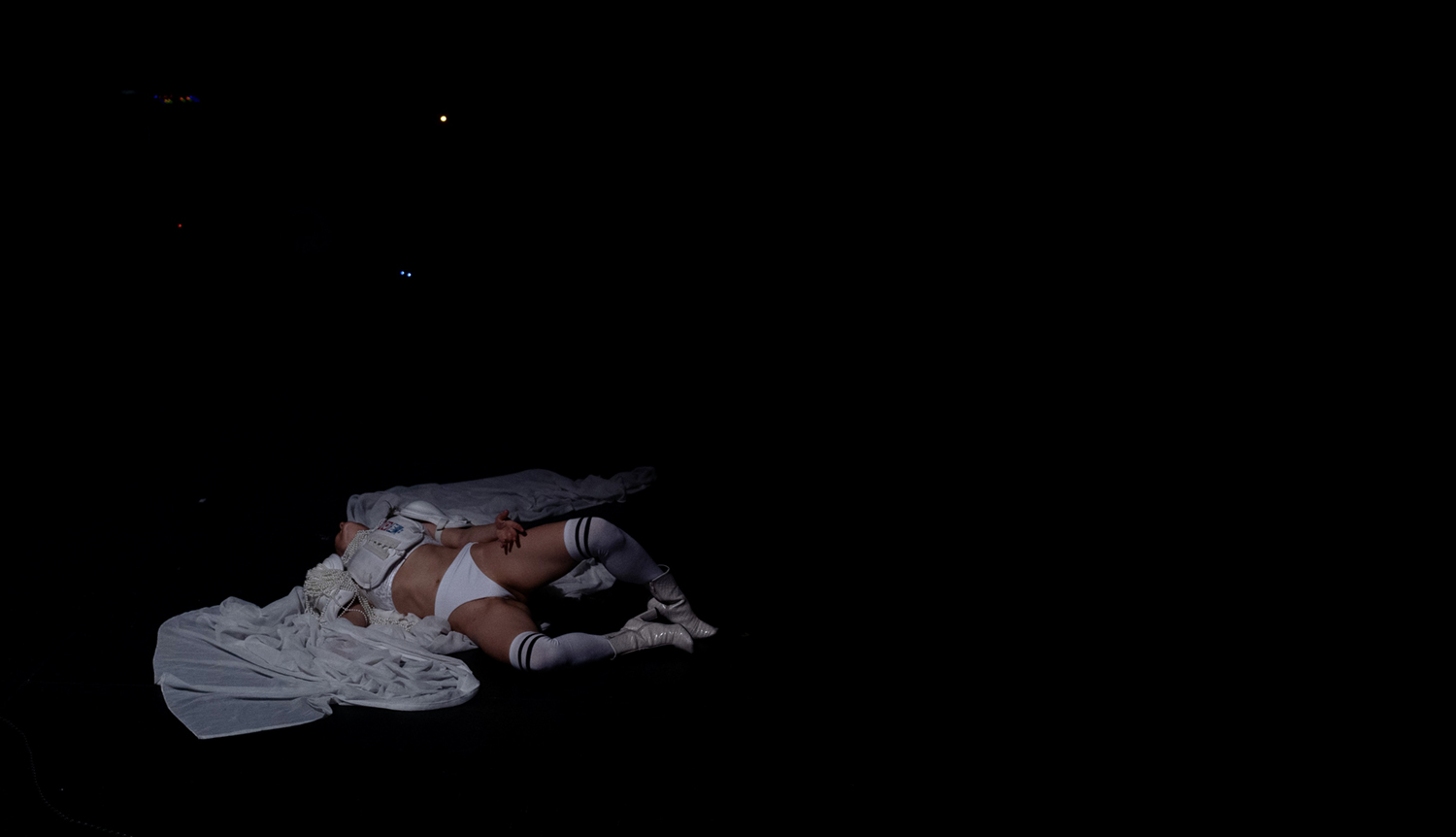

If the doomer, doomscrolling his apps for hours, imagines doom as the end times that are already vaguely here while everything goes to hell, Layton Lachman’s and Samuel Hertz’s doom does something like the opposite: doom, here, is transposed to being a place, too — an environment not only for cynically panicking about what’s next but also for sticking to a wide range of messy feelings attached to loss and grief. doom leaves space for not just the work, but also specifically the footwork of mourning to pop up, which at times might look like a teetering dance and heavy breath from under a lace mask. At other times, it might be dull, repetitive, endlessly riding a bicycle in the figure of infinity. doom is a place filled with fog machines: obviously. As you enter through the clouds, a world emerges in which remnants of a drone metal concert overlap with silly cult-ish elements, cool moves from the rave, bondage scenes. Which sounds like a lot – and it is! – as in, in doom things can be a lot without hinging on an aesthetics of overpowering. The performers, who are also in doom, are given space to do their thing as they move through loss, clutch their pearls, and pretend to play their guitars – anchoring everything in a sense of doom not as something judgmental and distant, but as something that could be or has to be lived through. And living through it also means figuring out how to be somewhere in-between being alone and being together, personal and political — a mediation that is partly aesthetic. As Fred Moten said in “The Black Outdoors,” in conversation with Saidiya Hartman: “Anybody who thinks that they can understand how terrible the terror has been without understanding how beautiful the beauty has been against the grain of that terror is wrong.”

Any kind of loss challenges not only one’s sense of balance but also one’s sense of scale. Loss, which is almost always ongoing, can feel as if it’s the only thing that has ever happened, the only thing that is still happening. In the middle of capitalism’s violent abstractions, this is why it quickly becomes the object of economic evaluation. What kind of grief is adequate for what kind of event? How financial is a loss, how sentimental the value appraised to its objects, how societal its cause, how private its handling? Rejecting this attempt to, however abstractly, put a price-tag on grief, the world of doom is an infrastructure to, on the contrary, suss out the possibilities within an affect that is out-of-scale. Here, a melodramatic guitar pose, played for others, or with them, or on your own, becomes a way to experiment with relation and proportion, to push a glacial sense of time into proximity with an intimate sense of time. This is how, in the world of doom, a personal proportion of crisis is given room to wiggle next to a crisis on a global scale, the climate catastrophe – without relativizing the two nor reducing one of them to the other.

With such divergent velocities and vibes, sound becomes one of the tools in doom to create a mood that functions as a holding environment for both, say, a tiny choreographic joke and the heavy mood that is the elephant in the room. In order to do this, the doom music, composed and brought to the stage by Samuel Hertz, extrapolates specific styles of various contemporary genres: doom metal, slow-burning and drone-y, as well as clubbier sounds. At one point, an actual Viola da Gamba is played against a hyper reduced pulsating synthesizer. The commitment to techniques of loudness and their mediation of catastrophe, however, precedes the 20th century subcultures that some of these sounds were mined in. In a note on doom, Samuel Hertz traces this interest back to the mid-19th century where intense noise (e.g. in the London Cyclorama) was used to give an impression of the Lisbon earthquake a century earlier, to the other side of Europe. Similarly, doom sounds out the various distortion effects of loss – beyond scandalizing it – as it travels across choreographic timing and performance space.

In the world of doom, there are times when the sound thins out and the performers come together in a circle in the middle of everything that is happening. They wait for and check in with each other, put their arms over each other’s shoulders and while moving their whole bodies up, begin to sing, never unisono, with slight delays and dissonance. Somewhere in-between somatic practice and casual composition, it becomes clear how the sonic dimension of doom extends to embodiment. The heavy guitars, too, and their rich iconographic history of sexy posing have fermented into ways of moving through time: headbanging becomes a way to walk. Offering your instrument to the gods of metal turns into a way of repetitive, stuttering secular dancing. First, you point like a rockstar would point into the sky above the stadium and suddenly you’re pointing everywhere and everywhere points right back.

Next to Layton Lachman and Samuel Hertz are Caroline Neill Alexander and emeka ene. doom lends itself to the performer’s idiosyncrasies, underlined by their costumes (designed by Ivanka Tramp) that each encapsulate an endlessly specific vibe: an oversized non-binary suit, the most ultimately ripped double denim fit, NFL-esque protective gear with integrated trinket, a fiery wig that offers refuge. Style, in a utopian rock band, or in doom, means to negotiate personal preferences and collective endeavors. Enter a scene where the performers are chained to one another, making literal the bondage-y entanglements that have long constituted the collectivity that is at stake.The mood, or rather mood swings, that doom so carefully crafts can be festively sad but nobody here mistakes grandiose self-seriousness for depth. In its commitment to actually being genre – not just metal, but also dance performance – at least a little bit rather than just conceptualizing it, doom also embraces social practices that suspend judgment on what would be an adequate, appropriately scaled darkness. In doom, precisely in the wake of all-caps poses, mourning is casual. Mourning, glamorously, rocks. That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily any easier, but a shared space, even or especially where it doesn’t always amount to a whole, offers a kind of solace.

Doom nudges mourning onto the stage of loudness and glitter, gently peeling off its shock value. Every so often, a midbrow journalist writes a think piece on the “lost” or “dying” “art of mourning,” usually portraying rural, indigenous, and various supposedly other social practices as the place where it can still be found. As Kathryn Yussof writes, the nostalgia around those is not just an accidental side effect of Western alienation. Indeed,“imperialism and ongoing settler colonialisms have been ending worlds for as long as they have been in existence.” Any attempt to grasp the extent of feelings of the end times as personally lived, “climate grief” if you will, is dependent on the work of mourning for Black and indigenous worlds that have already ended, are still constantly ending. Without spelling this out – it’s unspeakable – in doom, it is the affective premise; for most people, the end times have long arrived. Hanging out and even potentially having a great time here entails an obligation to not leave the aesthetics of the end of the world to doomscrolling and apocalypticism. “Let’s start,” Yussof cites science fiction author N. K. Jemisin, “with the end of the world, why don’t we?”

Tickets to doom at Tanztage in January 2022 can be found here, and here is a playlist they all made called “Sounds of doom.”

Words by Maxi Wallenhorst

Images by Ethan Folk

Maxi Wallenhorst is a writer living in Berlin. Recent essays have appeared in e-flux magazine and Texte zur Kunst.